Spreading the light

the MAOZ Network members during the pandemic

Spreading the light

click on a photo to read the full story

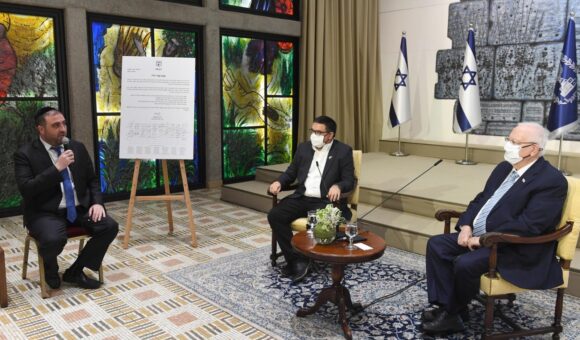

Increasing Trust Through the Media

Two groups in Israeli society have been particularly affected by COVID-19 and the media coverage they have received throughout crisis: the ultra-Orthodox and the Arab societies. MAOZ launched an initiative in collaboration with Network member Eitan Zeliger to improve media coverage

During the COVID-19 crisis, Israel’s mass media, which had previously ceded much of its influence in favor of social media platforms, once again assumed a central place in the public arena. The public approached mass media outlets in search of reliable information; decision-makers appealed to the public through the news, and ratings shot back up.

But when the public sits at home and receives its information from the media, everything that is presented becomes fact. And when the public and societal leaders are fed an unreliable snapshot of reality, decisions are made that do not match needs in the field, going so far as to even harm citizens.

Therefore, at the peak of the COVID-19 crisis, following the negative reports that the ultra-Orthodox were not adhering to the guidelines, the mayor of Ramat Gan announced the construction of fences between his city and the nearby ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak in order to prevent residents from passing back and forth.

These two cities are so close to each other that one building may be situated in Bnei Brak while the one next door is already in Ramat Gan. The mayor’s extreme step did not have any health ramifications – the virus clearly does not stop spreading when it reaches a fence. However, the decision illustrated the public’s negative opinion of Bnei Brak in particular, and the ultra-Orthodox society in general.

The result was a huge crisis of trust between all the citizens of the State and the ultra-Orthodox society, and between the ultra-Orthodox society and the rest of the public and the media, whose work had instilled the public’s sentiments.

MAOZ Network members also felt that the reduced trust harmed them even more than the COVID-19 consequences themselves. As an ultra-Orthodox Network member said then: “I admit that in recent days I’ve already thought about the value that trust, which is engraved on MAOZ’s flag, has if not for a situation such as this. And I thought it would be better not to write in Whatsapp groups, as doing so would be a waste of time. I admit that I felt this way”.

And with that, the Cornerstone media initiative was launched with the aim of changing the coverage and public opinion towards the Arab and ultra-Orthodox societies. This was carried out through media exposure, in which we promoted COVID-19 heroes and shared stories about the ultra-Orthodox and Arab societies.

The initiative was led by MAOZ, in collaboration with Network member Eitan Zeliger, who owns and runs a public relations firm. The main and active partners in the initiative were the Arab and ultra-Orthodox Network members; they provided potential ideas and interviewees, with some even being interviewed themselves.

During its three months of activity, the initiative produced 25 published and/or broadcasted news segments about the Arab society. One of the initiative’s focuses was on Arab interviewees, and it included a series of interviews about Ramadan, which had previously been almost completely absent from the Israeli media.

31 positive news segments with ultra-Orthodox interviewees were also published and/or broadcasted. They delved into the effects COVID-19 had on the ultra-Orthodox society’s daily life, including the impact on businesses and students’ return to school.

20 Years Later – Pulling the Industrial Park Out of the Mud

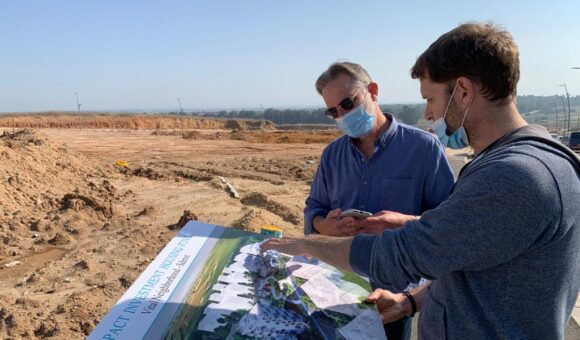

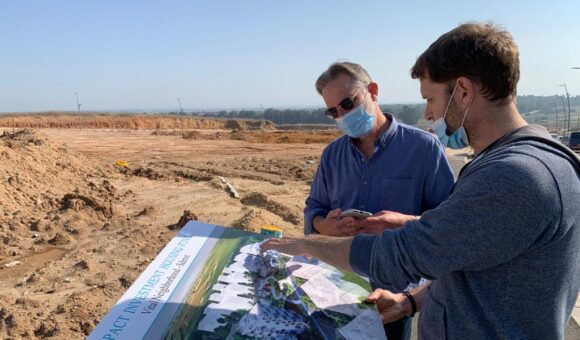

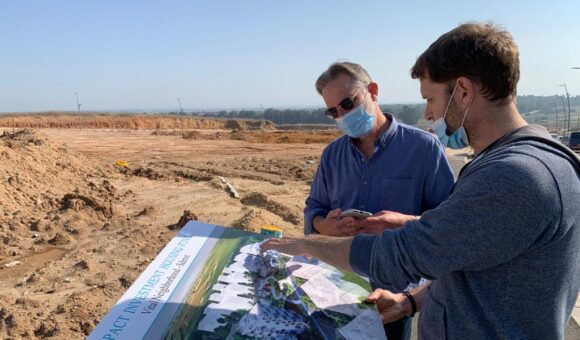

1.5 billion shekels. That’s the price the residents of Gezer, Modi’in and Ramla paid for the lack of cooperation between the municipalities. Now, Gezer Mayor Rotem Yadlin is trying to change that

“I’ll begin by saying this is a moving occasion for me. As far as I’m concerned, today we are changing direction, making a fresh start, building our future. After 20 years of paralysis, we are embarking on a new path – a path of growth. All of the forces on the ground are joining hands to work for the mutual benefit of our communities of Gezer, Ramle, and Hevel Modi’in.

When I first began as my term as Mayor of the Council, I surveyed the territory zoned for the Ramla-Gezer-Hevel Modi’in Industrial Zone. All I saw were ploughed fields and a lone tractor. As far as I was concerned, that tractor was ploughing the future of Gezer, its potential and that of Ramla.

Over the past decade, the local authorities lost a combined total of 1.5 billion shekels in property taxes. That’s one-and-a-half billion shekels that belong to the residents of Gezer and Ramla. That’s money that should be going to our schools and our infrastructure. Those taxes represent services that ought to be going to our residents, and they’ve been lost. This is a tremendous loss.

Today we confirm the end of this age of conflicts between the different local authorities and the beginning of a decade of joint investment to collectively boost this region.

So what does that mean? How did we do it? We simply stopped fighting.

We ceased quarrelling over who owns this or that piece of the pie. We threw all of the problems into the pot, and instead of talking about each issue separately, we discussed all of the issues together. We brought all of the problems to the negotiating table in order to create a comprehensive outline for a solution. This is what we are presenting to you today.

All this allows us to create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. A win-win situation. Today Gezer and Ramla are taking a leap forward together.

We are marching towards a decade of joint endeavors. Today, we will approve the collaborative development of the industrial park, which is the flagship project of the Central District – 30,000 jobs stretching across 2,161,566 square meters of construction permits. All of this immediately translates into property taxes totaling NIS 60 million for Gezer and NIS 90 million for Ramla. Whichever way you look at it, we’re talking about a serious growth engine. We’re promoting Gezer and Ramla and getting ready for take-off – in employment, transportation, and infrastructure. I see this as a joint decision to work together for the general good of the entire region.

This council meeting is just one step of the process; a lot of work and stages remain in this collaborative effort between Ramla, Modi’in and Gezer. We’re sowing seeds for years to come. This is our duty in local government, to plan and do whatever it takes to fulfill the vision.

When Everything Else is Uncertain, My Job is to be My Residents’ Rock

For Tal Ohana, Mayor of Yeruham, the pandemic was a crash course in leadership. She came up with creative solutions, took brave decisions and found new opportunities

“I’m Tal Ohana and I’m 36 years old. I was born and raised in Yeruham and I’ve been involved in local politics for about a decade.

While serving as Yeruham’s foreign leader for over a year, I handled strategic actions that dictated social, economic and educational resilience. The COVID-19 crisis was what ultimately transformed me into a leader who is very connected to her residents.

I informed each confirmed COVID-19 patient that he or she had been infected before the relevant authorities did. I didn’t want to wait. I did it in-person in order to ensure that they would be at home, where they wouldn’t be able to infect other city residents. I wanted to make sure that they had everything they needed for the isolation period. It wasn’t easy.

I had one conversation with someone who had potentially been infected and therefore had to undergo a test. It was five minutes before Shabbat. I keep Shabbat, although that hasn’t been too true lately. And she told me, ‘I’m not letting these testers into my house until you arrive.’ This sentence made me feel that at the end of the day, I am responsible for to each resident’s personal sense of security.

My role and responsibility towards the residents has accompanied me throughout this period, especially when it comes to trust. It was clear to me that during this crisis, when my residents were in a constant state of anxiety and uncertainty, I had to instill in them a sense of trust. My job is for them to know and feel that their city is being managed; that things are under control. That we’re operating, on top of things, and here for them. This is what increases their resilience and ultimately bolsters our resilience as a municipality.

I think this is something I’ve learned and I’ll hang on to it during both the emergency routine and the general routine.”

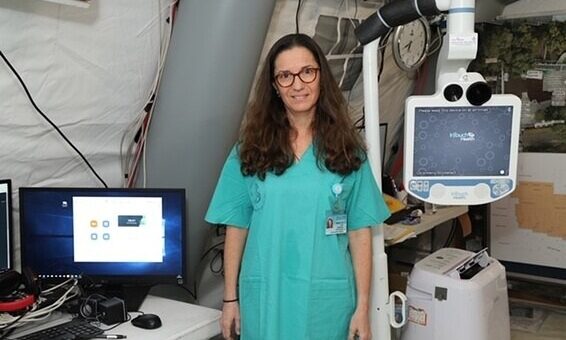

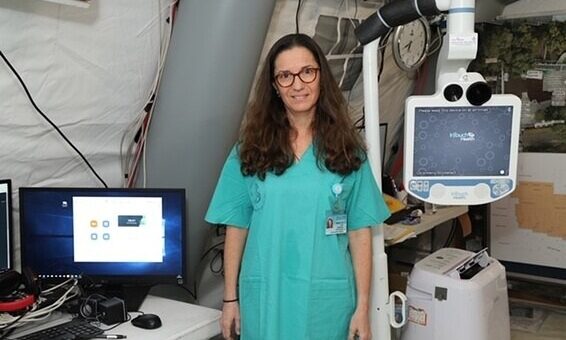

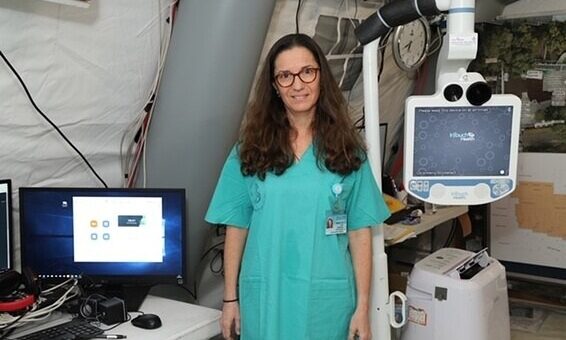

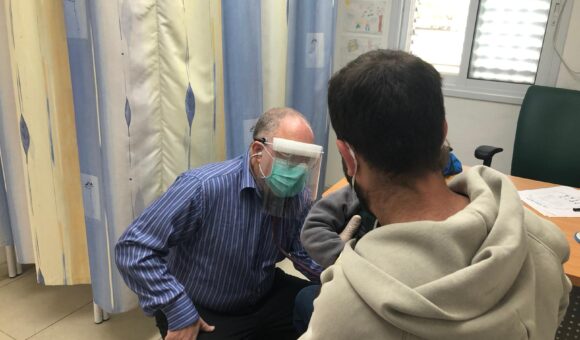

The Solution that Brought the Medical Staff Peace of Mind

Immediately after the coronavirus outbreak, as healthcare teams faced increasing stress and concerns, educational frameworks were set up for the children of medical workers in Northern Israel thanks to a special collaboration in the Network

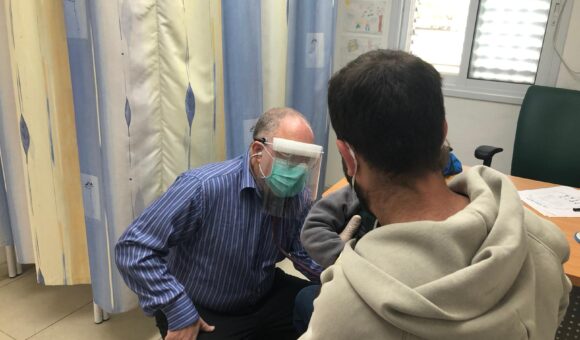

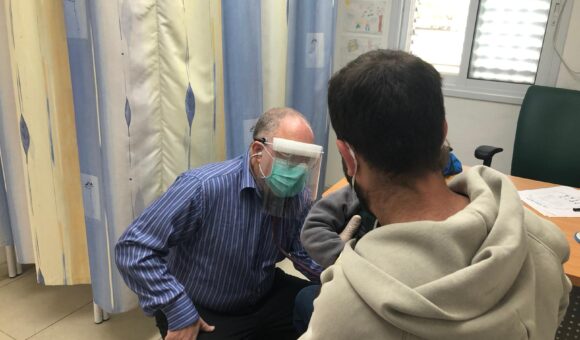

With the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, medical workers found themselves on the front lines. They were able to cope with working round-the-clock in conditions of uncertainty and with insufficient protection. But they faced an additional challenge that made it hard for them to focus on their professional duties, which were already intensive, difficult and tense enough: the closure of the school system and the ban on seeing family members that left no solution for their children, who were home alone during the shifts of these most essential of workers.

In response, the healthcare system, education system, and local government tried to bridge the gap. At the same time, there began a focused and rapid collaboration between two members of the MAOZ Network: Hagar Mizrahi, the former Acting Director of Poriya Hospital, and Eli Meiri, the CEO of the Kineret Amakim Cluster.

They had not met each other before, but belonging to the MAOZ Network opened the door and paved the way for them to produce a quick, focused, and meaningful solution for medical staff’s children.

There’s a Bright Side to Testing Positive

When Riki Siton tested positive for COVID-19, she mainly felt alone. Before the Bnei Brak resident even understood what was happening, she was in a taxi on the way to a hotel, where she would isolate. Now that she has recovered, Riki’s mission is to help other infected patients feel less alone

I tested positive.

It happened on the first of the month of Elul. It’s a day filled with excitement in the ultra-Orthodox society, as children begin a new year in their educational frameworks and we, the parents, get to have some time for ourselves. The first free moment I had, I asked myself how I was feeling. And the trust was that I didn’t feel too well.

I picked up the phone to the doctor, received a referral for a test and tested positive for COVID-19. Thoughts began swirling around my head: how did this happen? Who did I meet? Who did I infect? How many people will have to quarantine because of me? How will the 11 of us quarantine within four walls? Do we even have enough food? (The answer by the way is no. Quarantined children at home are insatiable).

The whole family began quarantining together and everyone was tested. Some had even managed to be infected. Then the phone rang. “Go to a hotel; it’ll reduce the infection,” they said.

I had a lot of questions: What is this hotel? What does it look like? Can I take my daughters with me, even if they’re not infected? How will I do laundry? Is there enough food there? There were almost no answers. They just told me that they’d be by to pick me up in half-an-hour.

I remember feeling uncertain on the minibus ride to the hotel. Once I got there, I met many other families feeling the same distress and uncertainty – in the entrance, registration, hallways and in between the rooms.

When we got home, my phone was filled with phone numbers of the people I met. We started a WhatsApp group “COVID-19 Hotels” and people started adding more and more people themselves. Groups of hotel “graduates”, patients on their way there, and also those who are currently at the hotels also opened.

Tips, recommendations and questions – it all flowed in the group. We even wrote the “COVID-19 Guide for the Beginner”.

But then I realized that something else had happened here: we had created a special group of COVID-19 patients who had recovered, and maybe something else could be done. So I opened a new WhatsApp group called: “Recovered COVID-19 Patients Volunteer.” I asked them if they’d like to volunteer and whether they’d like to use their advantage for good.

When a lot of people showed interest, I went to hospitals. I asked them if we could help them at all – we, the recovered COVID-19 patients. When someone is hospitalized in the COVID-19 ward, family and friends can’t visit him or her, and the loneliness only adds to the fear of the disease. Support is a must.

It isn’t easy to create a group of volunteers in the hospital, and it usually requires a lot of bureaucracy. But because of the period and the opportunity, we were able to move things along quicker. And just like that, 263 volunteers arrived (in full protection) or are waiting to be sent to hospitals.

In one of my conversations with the hospitals, I spoke with Network member Sefi Mendlovic, VP of Sha’are Zedek. “Do you need volunteers who have recovered from COVID-19?” I asked. “Yes, and we already have a lot of ultra-Orthodox volunteers. If, for example, we had more volunteers from the Arab society who could speak to those who are hospitalized in Arabic, it’d be a great help. “

I picked up the phone and called MAOZ. Within a few hours, we created a questionnaire looking for Arab patients who had recovered from COVID-19. The Arab society then also began moving things along on their own and we have quite a few Arab volunteers.

In this difficult time, this is what I think makes all the difference. Right now, when everyone is busy with earning a living and maintaining one’s strength and health, we can mobilize forces from within.

We’ll get through COVID-19, and I really think it’s going to be thanks to working together.

We Turned the Entire City into One Big School

Students learn at the park, the river, the museum and the beach. Osnat Saporta, VP of the Hadera Municipality, and Shlomi Dahan, Director of the city’s Education Division, tell how they realized, before everyone else, that the current school year must be conducted outdoors

“When we started planning for this school year, we realized that it was going to look different. Last year, just before the school year ended, we invited the educational staff, principals, parents and students for a consultation. We looked at the months that had passed and we thought about the coming months.

We heard one clear-cut conclusion from the distance learning experience and a request from them: Don’t let screens replace personal, social and educational encounters.

So together we broke out a new educational model, adapted to the spirit and the demands of this period of social distancing. The model enables learning to take place not only on screens at home and addresses the fact that schools do not have enough space to meet the requirements of social distancing.

We turned the whole city into a school, a complete learning space – the urban park, Hadera river, the beach, the museums and the city streets – they all provide space for city students to continue their education and learning routines. We believe this effort will be copied by other localities; it’s a joint effort by all of us to find the way to be here for our students – face to face.”

Amdocs’ High-Tech Workers COVID-19 Hotline

Overnight, banks, municipalities and others shifted their call service centers to the internet. But what are older people, many of whom lack the necessary technological orientation, supposed to do? Gali Shachar Efrat had them in mind when she established Amdocs’ employee-run hotline

“When the COVID-19 outbreak began, the call center we had opened at Amdocs collapsed.

It had only opened a few days prior, following a post I had read in a Raanana residents Facebook group. One of the elderly residents wrote: ‘My bank branch has been closed and I have no idea how to work their digital app. Can anyone help?’

As a member of the Raanana City Council, there was nothing I could. But I realized that my job at Amdocs provided us with an opportunity to intervene.

Within a few hours, Harel Givon, our Division President and I sent an email to all Amdocs employees, saying: ‘Amdocs is setting up a virtual hotline to support residents who have difficulty dealing with technology. Your knowledge is an asset to them. We would be happy if you would like to take part.’

We then contacted the residents through the Raanana Municipality, other local authorities, NGOs, aid organizations and the Ministry of Social Equality.

We sent 8,000 messages to all residents over the age of 65: ‘Do you have a problem connecting to Zoom or having a video call with your grandchildren? Amdocs has opened a call center to help you out.’

We weren’t expecting to receive so many reach-outs, and our hotline initially couldn’t handle the load.

But this was also a key moment for us, as Amdocs employees enlisted en masse and our Digital Friends initiative was born.

I’m old and new at Amdocs at the same time. I recently returned to high-tech after working in the social sector for years. When I first returned to the office, one of the managers approached me and asked, ‘Will you teach us about the social world? What should we do differently?’

I’m not sure he understood how seriously I took his questions.

Amdocs has always seen itself as a leader in corporate responsibility. We feel we’re frequently giving a lot back to the community: painting schools, packing food baskets, etc. There’s no doubt that all this work is truly significant.

But I’ve always asked myself: why don’t we contribute the thing we know to do best to the community? We’re a leader in the production of digital solutions – this is what we need to give back to the community.

I didn’t know where to start, but then the biggest opportunity I could have imagined arrived: COVID-19.

The first event we took part in as part of the Digital Friends initiative was Memorial Day.

Thanks to MAOZ Network member and then-General Manager of the Israel Association of Community Centers, Raz Frohlich, we realized that entire families were planning to hold this year’s commemoration ceremonies on Zoom. Their great desire to share the most precious thing of all – stories about their fallen loved ones – hit a bump in the road when it became apparent that most people lacked the necessary technological knowledge and familiarity with the required platforms. This is where we entered the picture.

Everyone who contacted our hotline received close accompaniment: 200 volunteers accompanied families throughout the process – from the scheduling stage until the end of the evening. We wanted to help families socialize with their loved ones rather than mess around with technological issues.

We received hundreds of responses from families and participants.

But the most surprising responses of all came from our own employees, who didn’t leave the calls until they had all ended.

That night, at the end of a long day, I sat on the couch and began reading the reactions of all the employees who had volunteered at the hotline.

‘Personally, this a very difficult day for me because of my experiences. But this time around, I experienced it in a moving and different way,’ one of the employees wrote me.

I couldn’t help but cry.

I realized that at a time like this, when our employees themselves faced such uncertainty, we were able to create a sense of meaning for them. They were part of the solution for thousands of people, and they drew a lot of power from the experience.

The COVID-19 crisis has shaken us all, even in the high-tech world. But for us at Amdocs, this has also been a year with a big bright spot, at the end of which we have emerged with a new understanding of the role the business sector plays in Israeli society.

We can be much more than a place of employment, and we can also contribute more than packing food baskets. We can help the community deal with technology, and we will instill this perception in our business thinking moving forward.

And the hotline? It’s still running, and you’re welcome to refer us to people who need some help. 200 Amdocs employees are waiting for them, ready to make a social change.

Learning Hebrew in East Jerusalem Requires Partnership

Learning Hebrew can open doors for children in East Jerusalem. But for some of them, Hebrew comes with negative political and historical connotations And others simply do not have the opportunity to practice the language in their environment. That was why members of the MAOZ Network from the Ministry of Education and the Jerusalem Municipality led a joint trip to solve the puzzle of how to work together and bring about a revolution that could improve the children’s lives

What is the difference between a child living in East Jerusalem who learns Hebrew and one who doesn’t? Opportunities. The language opens doors and paves paths forward. A child who learns Hebrew increases his or her chance of finding employment in the Western half of the city as a teenager or an adult, and he or she will be able to go on to universities and colleges upon finishing school. And even before then, in activities and trips to the shopping mall, a child who has learned Hebrew will have access to the language that surrounds them. That is what guides us when we talk about learning Hebrew in East Jerusalem.

For this reason, the Ministry of Education and the Jerusalem Municipality are working to implement a comprehensive program to teach Hebrew in East Jerusalem. It’s a complex and sensitive mission.

Do the children want it? The parents? Is there a price to learning Hebrew for the children of East Jerusalem? And how do you bridge the gaps and overcome the obstacles? Is there any way to know if it’s being done right?

Behind the scenes are two separate organizations charged with this mission, which include a number of Network members among their ranks: Yaffa Yashar, Regional Coordinator for the Jerusalem District at the Ministry of Education; Lara Mbariki, Head of the Arab Education System in the Jerusalem Municipality’s Education Department;

Yoav (Zimi) Zimran, Deputy Director Jerusalem Education Authority, and Zion Regev, Head of the East Jerusalem Five-Year Education Plan.

In August, the Ministry of Education and the Jerusalem Municipality set out on a joint trip to begin work on two missions: the first was to identify solutions for teaching Hebrew in East Jerusalem, and the second was to create a successful working infrastructure for the two different yet complementary organizations so that they could work together.

One of the participants on the trip spoke about the complexity of learning the language and using it as an adult: “When I came to Tel Aviv, I worked in a restaurant on the ground floor of the shared apartment I lived in. Someone asked me for a keisam (a toothpick). I remember standing in the kitchen of the restaurant, looking up, down and to the sides. I felt lost. What is a keisam? I learned Hebrew standardly, and yet still when it came to the moment of truth – I was helpless. What is a keisam?”

At a consultation meeting with education officials from the community, one educator made a request that doubled as a statement: “You have a responsibility to find ways to improve on the way things have been done so far.”

“We see how other languages are taught, and what the motivations, challenges and opportunities are. We need to take it back upon ourselves so that we can see what we’re doing wrong, as well as right,” another participant added.

“If we learn to harness the power of working together on the challenge of teaching Hebrew, it might serve as a pilot for other programs that we’re working on together,” one of the trip’s participants concluded.

Following the trip, the participants set out to plan a series of experiments and trials in language teaching, with each taking charge of a different aspect in order to better understand the needs of the education system and the students and how best to teach the language.

We Hit Rock Bottom. Only Then, We Understood What’s at Stake

The second COVID-19 wave came in the middle of the wedding season, and Dr. Samir Mahamid, the Mayor of Umm al-Fahm, found himself calling dozens of newly-infected people every day

“When I first became the Mayor of Umm al-Fahm, I received an offer to participate in a special training course in the U.S. to prepare for emergencies on the municipality level. The vast majority of Arab municipalities didn’t understand the need. In Arab society, emergency situations seem irrelevant since during wartime, we’re not a part of the story.

But I decided to go. And I already realized then that our main problem in routine times would become much greater in times of emergency; that is, our inability to work in synergy in and amongst ourselves. Every department and every organization in our city works alone. No one sees the next door neighbor who may be doing the same as you or building on your work. I didn’t know how to approach such a complex issue, how to make clear how much we’re missing when everyone sees only their small part. Then COVID-19 happened.

It’s now been exactly two years since I became Mayor of Umm al-Fahm. I’m not originally from this world – I’m not a politician. I’ve worked in education my entire life. I went through the whole track from teacher to principal to mentoring principals. I decided to run for mayor because I felt that our city deserved different leadership. When I won, I sat down and started learning everything from scratch. What a municipality is, how to make decisions. We had an 80-million-shekel deficit. I started with damage limitation, understanding which things we could deal with and what could wait.

When the first wave of COVID-19 hit, we Arabs proudly proclaimed that it hadn’t reached us, that the Jews were the only ones getting infected. Even the outbreaks in Umm al-Fahm were as a result of meetings with Jews, and we managed to keep them under control very easily. We acted fast, closed mosques and collaborated with religious leaders. We asked residents to go into lockdowns and they listened.

After the first wave, the entire country relaxed a bit. We felt that we’d beaten COVID-19. The problem was that this lax behavior came precisely during the Arab wedding season, and the combination of the two resulted in an explosion.

It’s important to understand: weddings for us are events on a different scale than in Jewish society. We plan them one or two years in advance. So when I tried to convince people that they couldn’t have weddings now, that it’s a matter of life or death, I couldn’t get it across. We handed out 5,000 shekel fines, but organizers just calculated it into the budget as another wedding expense.

I felt I was losing control of the city. I was receiving reports every day and calling all the new patients in the city. By the end of August, we had 1,000 active cases, meaning dozens of phone calls each day.

I wrote a letter to Professor Ronni Gamzu and the Minister of Health. I asked them to open wedding halls, now of all times. We can control wedding halls and we know exactly who to penalize. But when weddings are held in people’s private courtyards, we don’t even have legal grounds to enter.

My request went unanswered. But one day they called and told me that Professor Gamzu and police chiefs are coming to visit the city. They expected me to scrub my office clean and take them to a community center that was handing out food packages. But I decided to use the visit to show them what was really happening on the ground. I took them to a wedding. They went in and were shocked. They couldn’t believe how disconnected the situation on the ground was from their instructions. At the end of the visit, Professor Gamzu came to me and thanked me. He said: “It was like being punched in the stomach”.

Now while we didn’t have many cases during the first COVID-19 wave, we were hit hard financially. We brought MAOZ in to accompany us as we worked with the small businesses in our city. We sat with them for the first time around the same table. We realized how many people the owners were keeping afloat, and we thought of ways to help them. All of the Municipality’s departments worked together guided by the data. My dream of working on our internal interfacing started picking up steam.

During the second COVID-19 wave, things looked different. We were a red city, so we started receiving help from all kinds of places. I went into a meeting with the Minister of Defense and came out with a promise to receive massive subsidies. We received money for epidemiological trackers, for food packages, for neighborhood coordinators and for public service announcements. We made many videos, one of which made a particularly big difference: we made a video of one of the residents who had lost his wife to COVID-19. He spoke from the heart and it had a significant influence in Umm al-Fahm and in the Arab society in general. The most dramatic moment, the one that made us all wake up, happened on September 1st. We watched the entire country go back to school while we were the only ones staying at home. It made people understand the situation. And us? We explained that it doesn’t have to be this way; that it depends on us.

I think that was the turning point. People started being more careful and they attended weddings less often. They began realizing that their actions have consequences. When we went back to school after the second lockdown, the first thing I told residents was that it’s thanks to them. We worked hard, we fought the virus and it paid off.

At that time, MAOZ started working with us again, and the main value we received from the process was the ability to disconnect from our desks and work together. What made the difference was not the information we received but the opportunity to work on our internal interfaces.

When I look at the brainstorming, the dialog and the way we listen to each other now—things that were missing before COVID-19—I think that with the right work, the virus can be a great opportunity for us all.”

The Young Bedouins Who aren’t Afraid of the Police – They Serve in it

Tent by tent, village by village, Yaron Matas went to convince young Bedouin to enlist in the police force.He’s convinced that

this is the way to create trust between the police and the Bedouin community in the Negev

“How many Muslim police officers are there in the Israel Police? And how many officers? And how many of them are Bedouin? This was my first question on my first day when I entered my new position as Deputy Director of the Administrative Division for Arab Society in the Israel Police, a division that was established to increase the Arab public’s trust in the police.

And here is the answer: approximately 3% of police officers and a minority of them are Bedouin from the south.

20% of the society but only 3% of the police force. It’s a little strange that we are talking about trust isn’t it? How? In what areas? On what basis?

We sought to find out the reason and we sought to focus on the Bedouin community. Why aren’t there Bedouin police officers in the force? Obviously, it’s complicated. There’s a story of identity here, a story of trust but also a big story of language. For people who don’t speak Hebrew, it is difficult to get any kind of job, let alone serve in the police force.

So, we decided to try to do something different – if its impossible to apply for a police officer job, we will build another step in the path: a preparatory program. We thought that if we created an intensive framework to teach language, we could create an effective springboard for police candidates. But how would we recruit candidates? A Facebook post was not going to solve the problem here.

So, we went tent by tent, family by family. We told them about the idea, we made the offer – come to the preparatory program and you will be able to have a position with us in the police force. And if not, maybe in the prison service? The fire department? Sometimes these are more accepted in the community.

When meeting one of the families, the father told us that language is the biggest barrier – and we realized we were on the right track. We saw how he was thinking ahead when he said that he dreams about his children’s future.

*We received 700 resumes. * In a selection process we chose 65 of them who began the preparatory program. We promised them it would be difficult – and we kept our promise. Intensive around the clock training that received a “bonus”: the coronavirus pandemic. We turned the learning routine over to them, and we helped them with solutions like computers that made it possible.

The preparatory program ended. Nearly 50% of the participants completed it successfully – and are enlisting in the police force. And what about those who didn’t? We have responsibility toward them. We called, we offered, we recruited them. We believe that with the knowledge and skills that they received in the preparatory program; they are suitable for the labor market. In cooperation with the Israeli Employment Service we are helping them find suitable workplaces.

When I stand at the ceremony, in front of 26 new Bedouin recruits, I am greatly moved. I look at each one of them and know that not only has he gone through a process to be here, we have too. At one of the entrance exams, he was almost rejected. The selection staff gave him a task: there’s a burning building and citizens are not allowed to enter. So, he grabbed the “citizen” and did not let him pass. He pushed him against the wall. On the task report it was written: displayed violence. That was the moment that I realized the change we need to make in the police, it’s not only diversity. It’s also what the diversity brings with it. It’s learning the story behind the people. Behind the way of thinking. Behind the statistics. We went back to the officer staff and explained to them that from his point of view he executed the task – and did it completely. It’s true, it’s not acceptable but is it possible to explain what is and isn’t permissible? To explain how? I believe it is.

And I am not the only one. That same young man, who is today a police officer, stood before me at the ceremony. With 25 other new officers in uniform. The calls from district commanders in the police force have not stopped coming, everyone wants these recruits in their district. This is clearly an opportunity for change. It’s clear that there’s an important force here, and that there’s willingness to adapt the system to accept these officers.

In a few months the second cohort of “Youth for a Secure Future” is starting. It’s not surprising that we encountered budgetary problems in funding the program. Thanks to connections to the Network, I was able to turn to the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of the Economy and the Welfare Ministry – to present the program and to request that they direct resources to it. And this succeeded. I received full cooperation from the Network members who connected to the idea and helped realize it.

I am waiting for the next ceremony. To see another new row of police officers excited, belonging, who return to their families with a sense of responsibility, who feel the role accompanying them and what it means to be a personal example. I know that they are our partners in the task.

And I believe – that if we are here to increase trust, the first step is in getting to know each other and connecting. From there it will be possible to create “another reality.”

How Hazmat Suits Created Solidarity in the Hospital

Not the quarantining nor the health concern. Dr. Ina Shugayev, Director of Haifa-based Fliman Geriatric Center, realized that the real danger posed to her staff was the feeling that they were alone even inside the hospital

“It was at the beginning of an evening shift. One of the nurses in the new COVID-19 ward we had opened came to work after a few hours of time at home. ‘Afraid of me? Do you think I’m contagious?’ she asked.

The staff members in our COVID-19 ward, like the other COVID-19 wards in the country, had been instructed that they were forbidden to walk around the rest of the hospital. They had to adhere to the hospital’s pods.

I didn’t know what to say. How can I face that nurse and try to explain to her that going home to see her family and the children is fine, but that at the hospital, she can’t hop over into another ward? If we trust the preventative system that ensures us a routine outside the hospital, why can’t we act the same way inside it?

At that moment, I made a decision. If the COVID-19 ward staff is allowed to go home, they’re also allowed to wander between hospital wards and congregate in common areas. It was not an easy decision, but as a manager, I knew I was responsible for the resilience of the teams who were working so hard.

The month the pandemic began was also my first month directing the hospital (I initially served as deputy for a short period). We opened the COVID-19 ward at the beginning of the crisis. It wasn’t required for a rehabilitative hospital to open a COVID-19 ward. Many of the operations in the ward are conducted remotely, but can anyone imagine treating a rehabilitative and geriatric person remotely? Feeding them remotely, or supporting the patient as he or she walks down the hall?

So our team felt refreshed handling emergency care; we put on hazmat suits, worked in shifts and kept doing what we know to do best: provide dedicated, personalized care. The Ministry of Health’s guidelines restricting family members’ visits created anxiety among my staff: how would they maintain their patients’ moods?

So I decided to allow visits, refining the guidelines. I trust that the families who come will do their best to not infect their relatives.

We cared for patients. But who will take care of the medical professionals? When MAOZ called to ask if we needed help strengthening the team’s resilience, I realized this was our mission. In examining our resilience index as a hospital, we were in a pretty good place. But my heart skipped a beat when I thought of one disturbing factor: a relatively low score in the dimension of support and solidarity.

The staff in the COVID-19 ward signaled that they felt separated and alone; that the hospital didn’t see them. They felt disconnected from the rest of the hospital, and the rest of the hospital felt disconnected from them. That was enough for me to understand that action had to be taken.

We decided that for two hours, all the hospital staff, no matter what ward they belonged to, would have to work with full hazmat suit protection. Just like the COVID-19 ward staff does every day.

The very next day, all hospital wards started the work day in full hazmat suits: the medical staff, the nursing staff, the support staff – and me. We asked everyone to take a photograph of themselves in their suits and share how they felt. They felt hot, clumsy and stressed; even the air conditioner didn’t help. But the message was clear: we’re all in this boat – not just one department. And we can’t allow ourselves to forget that.

The other benefit of this experience was that suddenly, the hospital workers realized that the simple cloth mask they had been required to wear at all times is nothing compared to a full hazmat suit; in fact, it was barely noticeable.

With this small step, we all disconnected for a moment from our personal difficulties, and we were able to think of someone else and identify with his or her difficulties

I can already imagine the day after COVID-19: we’ll return the hazmat suits to the closets; maybe we’ll even take off our masks. Only one thing will remain: a team that managed to produce solidarity in a difficult time. And this sentiment will stay with us, even for the challenges ahead.”

The Reflection That Began Atop Mount Sigd

Only in Ethiopia, during a trip with the MAOZ Network, did Lior Shtul, CEO of the Bnei David Institutes, realize that the Israeli story he knew was incomplete. Since returning to Israel, he has seen it as his duty to tell the missing story of Ethiopian Jews

“I remember that every year, during the white storks’ migration period, my father would raise his hands to the sky and ask the birds: ‘Is Jerusalem doing well?’ Shalev Wobo, one of the graduates of the Bnei David yeshiva I run, told us recently. He immigrated from Ethiopia with his family at the age of seven, explaining that ‘We longed for Jerusalem. It was a dream that we thought of every day.’

This is the first time we are telling the story of Ethiopian Jews to our students. This year, I realized that the Israeli story they currently have is an incomplete part of the greater Israeli mosaic, and we are starting to try to complete it.

I’m the CEO of the Bnei David Institutes. I have hundreds of students and thousands of alumni who currently hold key positions in Israeli society.

As a MAOZ Network member, I have participated in all the trips MAOZ has offered. My first trip was to Poland. It was a special experience, but one of the things I remember most is that even Network members whose ancestors were not from Europe experienced the journey as part of their own personal stories.

That’s why I decided to join the trip to Ethiopia – to get to know a story which I had felt was not my own.

I admit that before the trip, I thought I knew the story of Ethiopian immigrants. I thought that the State of Israel played the part of the hero by bringing the Jews of Ethiopia to Israel.

From the moment I arrived in Ethiopia, I realized that everything I thought I knew was simply untrue. For example, while I imagined the country as a dry desert, I found it to be amazing in its beauty. I thought I’d hear stories of heroism about the “rescue” of Ethiopian Jews – but I learned how for years, they had prayed to get to Jerusalem, and all about the long journey they took to get there. I thought that Mount Sigd was one mountain, but I discovered that each community simply climbed the highest mountain closest to it.

When I reached the summit of Mount Sigd myself, I felt something new. I felt a special experience, and at that moment I realized that there’s an untold story here. And so since returning to Israel, I have decided to start telling this story.

For years, there was hardly any mention in Israel of the holiday of Sigd. At most, we wished Ethiopian-Israeli students a happy holiday. But this year, we’re turning a new leaf. I want the students in our institutions to know the story of Ethiopian Jewry not as the story of another community, but as their Israeli story. And it was important to me not only that we celebrate the holiday of Sigd, but that we understand the meaning behind it.

A few months ago, we decided to set up a Bnei David podcast program, hosted by Netanel Elyashiv, an educator at the yeshiva (and a MAOZ Network member). This year, leading up to the Sigd holiday, I told my team that ‘there’s a story we have to tell.’

Shalev Wobo, our graduate, who immigrated from Ethiopia at the age of seven, agreed to share his fascinating story with us. He told us that Sigd is an opportunity for reflection. So this year, we’re also reflecting a bit on how we’ve told the story to date, and how we will tell it moving forward.

Unfortunately, our students will not climb Mount Sigd this year. They won’t experience it on foot like I did. But hundreds of students and alumni who have heard the podcast have heard a new story. They’ll continue learning about the Ethiopian-Israeli identity, as well as learning that these people are our heroes.”

It All Began with a Trip to Finland. Now it’s Changing the Job Market

A training program that will reduce the mentoring time needed for new employees, high-quality recruitment for Arab students These are only a few of the experiments with the potential to enhance economic productivity – made possible thanks to technical training reforms led by Tair Ifergan

The reforms taking place in the vocational colleges are among the most vital for the future of the job market. They are being led by Tair Ifergan, who serves as Head of the National Institute for Technology and Science.

The initiative, which is being accompanied by MAOZ, began over a year-and-a-half ago. One of the biggest challenges is building trust and creating partnerships between the government entity and college heads in the wake of years of tension and lack of cooperation. To assist with this, a joint fact-finding trip to Finland was set up. Tair hoped that the trip would help everyone drive through a reform that would connect vocational training to the industry’s needs.

The trip had a significant impact and helped the participants reimagine how such a partnership might work in practice, as well as how to create industry partnerships, and determining how to tailor training and education to its needs. To ensure that the findings would be implemented in practice, the participants were asked to outline experiments, beginning during the trip itself: which of their findings regarding the relationship between training and industry would they be implementing tomorrow morning at their desks?

MAOZ began accompanying six experiments, each different in scope: one was related to high-quality recruitment of Arab students and minimizing drop-out rates. Another focused on establishing a regional connection between employers and colleges in a given area. A third experiment examined updating the syllabus of subjects with high demand in the job market.

Even now, projects that began as experiments are changing the reality on the ground. That is the case, for example, with one of the experiments that examined updating the training program to make it more relevant for the job market. Following the update, one engineer at Strauss Group predicted: “In my opinion, the training will reduce the time it takes to mentor new employees in the factory by half: from 20 months to 10 months.”

Pharmacists Are on the Front Lines – So Why Aren’t They Being Protected?

MAOZ Network members warned of the infection danger pharmacists face, and within a day, an official decision was reached to provide protection for all of them

At the outbreak of the pandemic, hundreds of pharmacies across the country were categorized as essential services, and pharmacists continued working on a daily basis in order to provide service to the residents who needed them.

But unlike medical personnel, who received equipment to prevent coronavirus infections, the pharmacists were left unprotected.

With 70% of Israeli pharmacists being from the Arab society, Arab MAOZ Network members from the healthcare and activist worlds sent an urgent appeal to the Ministry of Health. They also took other supporting actions, such as raising media awareness, appealing to political parties, and putting direct pressure on policymakers.

And it worked: the Ministry of Health guidelines were amended within less than 24 hours, and the new document contains a clear ordinance regarding the protection of pharmacy staff.

When the IDF Came into an Ultra-Orthodox Neighborhood

What do you do when your neighborhood turns red? Yehuda Spitzer from the Community Administration in Jerusalem’s Ramot neighborhood talks about the day hundreds of uniformed IDF soldiers deployed among the ultra-Orthodox residents

“It was right at the start of COVID-19 when I got a call from a city council member. He sounded worried and told me in a very stern tone of voice: ‘The situation isn’t good. We need to act fast.’

There are two community administrations in Ramot: one ultra-Orthodox and one secular. So in the ultra-Orthodox administration, we set up a neighborhood Situation Room. We created a call center and advertised it all over the neighborhood. But we didn’t just pass on instructions, we also asked questions: ‘Are you missing food? Do you need to go out to get medicine? Does any family member need to leave for isolation but you’re concerned about it? Are you worried that one of your children has contracted the virus? Talk to us.’

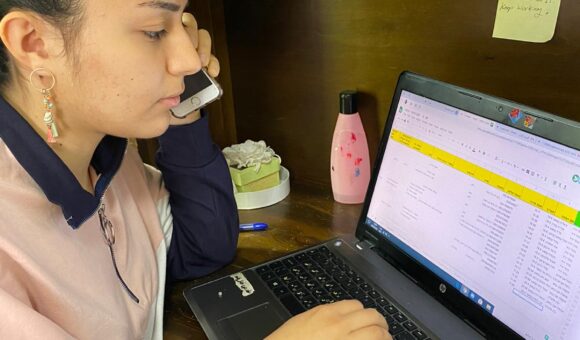

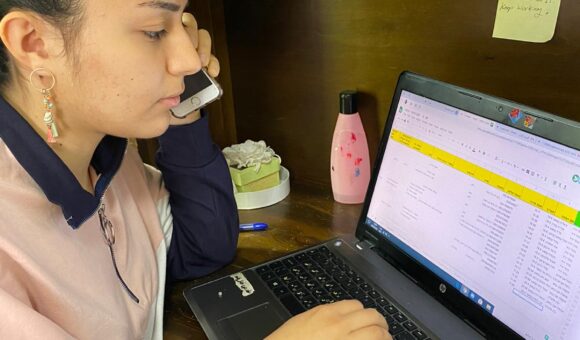

And they did. We entered all the reach-outs we received into an improvised Excel sheet and worked accordingly – this family needed a food delivery, that family needed help getting to the quarantine hotel, they needed medicine and we needed to check the situation in that building.

We saw that when a sudden crisis hits, two things happen: on the one hand everyone wants to help, but on the other hand, there’s so much chaos that it’s not always clear how. For example, how do we know where to send all the food boxes we had gathered? Who needs them? Who doesn’t? And is food really the thing that’s missing?

It demonstrated the Community Administration’s abilities and its important role in creating fast links to community representatives in the neighborhood. AT a time when everyone was trying to find a way to help, we found it.

We went through all the traffic light model’s colors here in Ramot: Green, orange and red. As we moved between emergency, routine and emergency routine, one thing remained constant: in order to deal with COVID-19, we had to keep our community involved.

And then the IDF Home Front Command called. ‘The neighborhood is turning red again,’ they told me. ‘There’s no alternative. We’re coming in.’ It’s not normal for military personnel to fill up ultra-Orthodox streets in our neighborhood. So we consulted the neighborhood rabbi, asking him what the right way to do this would be. ‘How do we explain this to the community?’

The rabbi recommended updating the residents so that they would be informed about what was about to happen. So we gathered the neighborhood rabbis (including some who don’t even recognize the State of Israel) and explained to them that because the situation was bad, the IDF Home Front Command would be coming in.

They passed the message on to residents. We gave people a bit of time to process it, and 24 hours later, almost 200 IDF soldiers entered into the neighborhood. It went smoothly, thanks to our coordination and cooperation.

That was just the beginning of our collaboration. To be able to help, the Home Front Command needed to partner with the community. For example, they asked us what the vulnerable areas in the neighborhood are, and so we immediately knew to send them to the bus stations to meet families and individuals travelling outside the neighborhood or the city, or those coming back from a family visit. We went down to the bus stations together. We told residents what was going on, explained and asked that they go back home.

After a few days, the Home Front Command continued on to Har Nof and then to other neighborhoods in Jerusalem. But I think that both our neighborhood and the military gained something from this challenging period – a lesson in collaboration.”

A Boy’s Dream, an Officer’s Vision

When Mevorach Avraham was appointed Commander of the police department in Kiryat Malakhi, he decided: the first meeting would take place at a youth village populated by young men who had been acquainted with the police for the wrong reasons

“Earlier this year, I returned to Kiryat Malakhi , the southern city I immigrated to from Ethiopia as a child almost 40 years ago. Only this time, I arrived as a senior policeman – the Commander of the city’s Police Department.

I believe that my connection to the city and its people is the story of this department and of our role. At the Kiryat Malakhi Police Department, we’re building a community.

The station typically kicks every week off with a situation assessment – a standard routine during which we update each other and conduct short-term planning. At my first meeting on in charge, I took all the police officers to a new space. We didn’t hold our situation assessment between the four walls of the police station that day. Instead, we met in a space that we had to get to know better.

Less than six miles away from the police station (a drive of only a few minutes) lies the Kedma Youth Village for at-risk youth. I thought this was the perfect place for us to learn about the impact we have on the people we serve and reflect on the significance of our roles; this was the space where we could personally hone what our roles are to ourselves.

We met with Shahar Rubenstein, the CEO of the youth village and a fellow MAOZ Network member, and teens from the village, as well. We heard about their experiences and charged encounters with the police, and we brainstormed about collaborations. This time, we, the powerful police officers, sought their assistance. For example, the next time we arrest a young man for his involvement in a low-level crime, maybe we can refer him to the village instead of opening a criminal case against him.

During this conversation, I turned to Yehudah, one of the young Ethiopian-Israeli men, and asked him: ‘What’s your dream?’

‘To start a family,’ he replied quickly.

‘And what are your expectations of us?’ I asked.

‘Let me be an equal citizen,’ he said to me just as quickly. ‘Speak to me in a down to earth manner.’

I remember that moment because I saw the looks in the eyes of the other police officers. That sentence stuck with us. Suddenly, they saw Yehudah, a young man with dreams and aspirations sitting in from of them. He wasn’t just ‘Y.’, a kid who had gotten mixed up in criminal activities. They realized that Yehudah has expectations of us, and that it’s our responsibility to meet them.

I hope that the meeting affected the young men as much as it impacted us. I hope they didn’t see a police officer or the Commander of the Police Department sitting in front of them in uniform. Instead, I hope they saw Mevorach, who had immigrated from Ethiopia to Kiryat Malakhi and looked exactly like some of them. I hope they saw that I’m a police officer who listens and cares and wants to learn from them.

When we returned to the station, it was clear to everyone that what we had seen in the youth village needed to be incorporated into our work plan. We had to figure out how to become police officers who don’t simply exercise our authority by virtue of our positions, but through seeing residents, teens and kids as people.

The reality won’t change so quickly. We will still see tension and racism in the world and among police officers. I don’t expect one meeting to change everything. But I’m sure that this meeting has blazed a trail forward for us.

I think of Yehudah, the police officers and myself, and it’s precisely during these difficult days in the already incredibly complex Israeli reality when I allow myself to dream. To dream of a reality in which young people of all backgrounds can see a police officer and not be afraid or apprehensive, but instead know that he or she is here to help them and our society.

That’s what fills me with hope.

Us and Them: During the Pandemic, We’re all in the Same Ship

Nir Bartal, mayor of Oranit, was concerned when his residents started asking: why are we allowing in residents from “red municipalities”? So he wrote a Facebook post, saying: in the Pandemic, we’re all the same

The original title for this post, which was written one week before the decision about the first lockdown, was meant to be: 40 Shades of Red. But the events of recent days led me to believe that it needs to be – “Us and Them.”

I planned to tell you about how two days before the closure began in “red” towns, I visited with two friends of mine, mayors of towns that are currently red: Rabbi Eliyahu Gafni, mayor of Emmanuel, and Mahmoud Assi, mayor of Kfar Bara, to support them and to think together how to cope with the coronavirus.

I planned to share with you the challenges they are facing: how do the residents of Emmanuel, most of whom do not have cars and use public transportation, travel to the corona testing point? How do they get a referral from their health fund when they do not have the app or internet? How do residents who do not have Facebook, WhatsApp or text messages get updates on guidelines? How has Kfar Bara managed to go nearly a month with only two confirmed cases and now, after 60% of Kfar Bara residents have been tested for corona, there are now 55 cases?

People have turned to me quite a few times with questions that begin with “us” and “them”. Why do we, in green and yellow towns, need to permit entrance to our town by “them” from red towns? Why can’t we, the secular, go to celebrate or to the country club…because of them, the religious? Why “us” the Jews…and “them” the Arabs? Why us the adults…because of the young people…?

True, there were not many such inquiries but there were some. I think that they show how we need to be careful. Careful with judgementalism, with criticism, with our angry statements about other people, other groups. It’s very “easy” to speak about us and them. It removes responsibility from us and distances us from unpleasant things. It enables us to define a group on whom we can place blame.

Behind every “us” and “them” are people. They are other but they too carry with them fears and concerns, exactly like ours. I have had the opportunity to speak personally with not a few of the ill people in Oranit (or at least with one of their family members). Among all of them was the fear – “we only hope that we did not infect anyone.” If you ask me, I have no doubt that no one (not of “us” and not of “them”) wants to become infected and no less so, no one wants to infect another. And the responsibility to ensure we do not become infected and do not infect others belongs to all of us.

I Realized We Can’t Wait for the Government. We Must Take Responsibility

The education system in Jerusalem is a microcosm of the country. Zion Regev, Director of the Five-Year Plan for the Jerusalem Municipality, tells about the moment when he realized that during the pandemic, their education system needs it’s own situation room.

“Jerusalem is sometimes a little like its own country – due to its size, and due to its diversity and uniqueness. We have 290,000 students in the city educational system. Ultra-orthodox, Arab, secular and religious. Children and youth from all corners of Israeli society are here with us in the city.

Our educational system, like the entire country, is going through a period of turbulence and uncertainty – and it comes in waves. Systems are opened and closed, there are infections, an increase in morbidity, a decrease in morbidity, quarantines. It’s all dynamic and it all needs rapid response.

In preparation for the beginning of the school year, we realized that opening educational frameworks brings questions, concerns, clarifications. The students, the parents and the educational staff had many questions that were bothering them: in what format will the year open – at school or with distance learning? What happens if there is a confirmed case in my child’s class? If my child is in quarantine, what do we do? If I am an at-risk teacher, what do I do? The answers to the questions are obviously dependent on policies, which in turn are influenced by morbidity rates. But what do we do in the meantime? What do we do with the vacuum created?

The vacuum created between decision making and the field, that is part of our role. We at the municipality realized that we had to enter this vacuum. We must be active.

So, we established a situation room for the educational system during the pandemic situation. We consulted with MAOZ about the situation room; they connected us with other authorities that already had active situation rooms. From there, at top speed, our new situation room was established.

An educational system situation room means an available, updated and connecting system. It means that the connection between health, education and the local authority is critical right now and here is a way to convey information, to raise challenges, to create solutions quickly, together.

The situation room has a role in cases of infection in schools. The moment we know about a confirmed case, we make sure that the person and those who were in contact with them go into quarantine as quickly as possible. Every day we create a local authority map of confirmed cases and people in quarantine in the educational system and share the information with the Health Ministry. The data and analysis that we share serve the decision makers at the national level. We realized that we are the only ones who know how to provide an in-depth analysis of morbidity in the educational system in Jerusalem.

We created a new system that synchronizes forces and is accessible to parents and to educational staff. Now we are a phone call away and they can turn to us with any question. This creates a sense of certainty and security within the great chaos. I think that this is our role.

Since then, I have spoken with members of the Network who are establishing situation rooms in their local authorities. We all understand that this is our role.

.

“Wearing a Mask is Fulfilling the Commandment to Preserve your Lives”

Moshe Adler, Director of the Haredi Sector at the Clalit Health Fund, talks about coronavirus patients who said goodbye to him on the phone for the last time, about the situation room he established in his home – and about the realization that observing the guidelines is, quite simply, a commandment

“These days, in my opinion, are very meaningful. There isn’t a building without coronavirus patients, there isn’t a family who doesn’t know someone who is hospitalized or, heaven forbid, no longer here.

In recent days I personally experienced several goodbyes over the phone with people who left this world. A member of the health fund who spoke about getting the coronavirus test at his home and two days later I went to comfort mourners. A young woman fighting for every word but begging: she is afraid to go to the hospital, afraid she won’t return, and requests treatment at home – which we cannot provide.

People who really deserve to go to a quarantine hotel cry to us to speed up the process with the Home Front Command. And these days I am the Front Command Room. Up until Yom Kippur began, I was working with the computer next to me to track tests that got stuck in some laboratory and you can “say kaddish” for them, to support people seeking mental health assistance, and to publish distancing guidelines; even on eve of the holiday.

The reinforcement that I feel is the call of the great men of the generation, may they have long life, from Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky and Rabbi Gershon Edelstein, who sent out a call again in an exact way. On the one hand they said: Wear a mask, even if it is uncomfortable, over your nose. Do not host or be hosted and pray as much as possible only in open spaces. And with this: preserve the atmosphere of joy and calm as much as possible at home and be strengthened through Torah study and Psalms.

It strengthened me greatly, the notice that what I am doing right now is simply a commandment, a mitzvah. Wearing a mask is fulfilling the commandment to preserve your lives (ונשמרתם לנפשותיכם””) A commandment!

And I hope that we shall merit to see the Messiah here, for through the hands of man, I don’t see the illness going away. So, I dream about the refreshing morning with the report of a cool breeze that gathers the coronavirus and it disappears…Amen!”

Operation COVID-19: Curbing School Dropouts

When there are neither schools nor Zoom classes, who will keep ultra-Orthodox students from dropping out of their educational frameworks? Yehuda Korenblit, Head of Beitar Illit’s Education Department, found a partner and embarked on a quick rescue mission

What does education look like in the ultra-Orthodox city of Beitar Illit during a prolonged period of emergency? When the COVID-19 outbreak began, only one educational institution in the city switched to online learning.

All other institutions knew they needed to keep up their respective learning routines, but the scale of the challenge required creative and effective solutions for managing a regular education system in homes blessed with many children but lacking computers and internet connections.

The education department’s task was not simple, but with a swift preparation process lasting less than one week, the various institutions set up a dedicated remote learning education system: instead of Zooming on computers, they used kosher phones. Children could use their phones to join voice-based sessions for personal conversations with their teacher while listening to recorded classes.

This method proved to be a rapid, high quality solution for thousands of students in Beitar Illit. But we knew that there were still hundreds of students caught in the middle who were not participating in the phone-based sessions for all kinds of educational, emotional and/or social reasons. These 300 students were defined as being at-risk of covert or overt dropout, as they had been left without educational frameworks even before COVID-19 hit. Some of these students found themselves alone with no educational framework to support and guide them in these challenging and sensitive times.

King Solomon, considered the wisest of all, had provided the solution for times of crisis such as these when he said that the best advice is to obviously receive advice. As he said, “In the multitude of counselors, there is safety”. I called a resident of the city, Menachem Bombach, the head of the Netzach education network and a MAOZ Network member. I outlined the challenge for him and asked for his advice.

We realized that the first thing to do was technical: reconnect these students to learning. So through fast collaboration, the charity set up a platform for dedicated distance learning. We raised funds to purchase equipment for students who needed it. We came to their doors, and every student who received equipment was also paired with an adult mentor to guide them and act as a point of contact during this period, while supporting their continued learning and narrowing the educational gaps.

Through this joint effort, we managed to retain a large number of students within a learning routine. An unusual routine, admittedly, bzut within a clear framework, which is so important, as we all know.

The challenges didn’t stop there. When I received my phone bill for the first month, I couldn’t believe my eyes: my own personal phone bill had come out to 1,000 shekels. And I wasn’t alone. All the families whose children were connected to domestic phone lines received bills for thousands of shekels.

Infrastructure collapsed pretty fast as well. We had always had phone reception issues in Beitar Illit, and now with so much activity on so many lines, the infrastructure was unable to handle the load.

The crisis also brought up opportunities for collaboration. First of all, within municipal departments, such as the collaboration between the education and psychological services departments regarding learning via phones or strengthening relations with parents. There were collaborations on the regional level as well, as a phone line and voice sessions were set up for the community center, for communities and youth organizations. There was further collaboration between the Municipality and government ministries, such as the Ministry of Communication regarding lowering the unexpected high costs.”

All other institutions knew they needed to keep up their respective learning routines, but the scale of the challenge required creative and effective solutions for managing a regular education system in homes blessed with many children but lacking computers and internet connections.

The education department’s task was not simple, but with a swift preparation process lasting less than one week, the various institutions set up a dedicated remote learning education system: instead of Zooming on computers, they used kosher phones. Children could use their phones to join voice-based sessions for personal conversations with their teacher while listening to recorded classes.

This method proved to be a rapid, high quality solution for thousands of students in Beitar Illit. But we knew that there were still hundreds of students caught in the middle who were not participating in the phone-based sessions for all kinds of educational, emotional and/or social reasons. These 300 students were defined as being at-risk of covert or overt dropout, as they had been left without educational frameworks even before COVID-19 hit. Some of these students found themselves alone with no educational framework to support and guide them in these challenging and sensitive times.

King Solomon, considered the wisest of all, had provided the solution for times of crisis such as these when he said that the best advice is to obviously receive advice. As he said, “In the multitude of counselors, there is safety”. I called a resident of the city, Menachem Bombach, the head of the Netzach education network and a MAOZ Network member. I outlined the challenge for him and asked for his advice.

We realized that the first thing to do was technical: reconnect these students to learning. So through fast collaboration, the charity set up a platform for dedicated distance learning. We raised funds to purchase equipment for students who needed it. We came to their doors, and every student who received equipment was also paired with an adult mentor to guide them and act as a point of contact during this period, while supporting their continued learning and narrowing the educational gaps.

Through this joint effort, we managed to retain a large number of students within a learning routine. An unusual routine, admittedly, bzut within a clear framework, which is so important, as we all know.

The challenges didn’t stop there. When I received my phone bill for the first month, I couldn’t believe my eyes: my own personal phone bill had come out to 1,000 shekels. And I wasn’t alone. All the families whose children were connected to domestic phone lines received bills for thousands of shekels.

Infrastructure collapsed pretty fast as well. We had always had phone reception issues in Beitar Illit, and now with so much activity on so many lines, the infrastructure was unable to handle the load.

The crisis also brought up opportunities for collaboration. First of all, within municipal departments, such as the collaboration between the education and psychological services departments regarding learning via phones or strengthening relations with parents. There were collaborations on the regional level as well, as a phone line and voice sessions were set up for the community center, for communities and youth organizations. There was further collaboration between the Municipality and government ministries, such as the Ministry of Communication regarding lowering the unexpected high costs.”

Behind the Masks, our Humanity Stands Out

Adel Iktelat, a senior Clalit HMO official, deals with the pandemic every day at work. Then one day, it hit close to home

“I’m Adel Iktelat, I live in Daburiyya and I’m the Nazareth Director of Nursing in the Clalit HMO’s Northern District and the Director of the Repeated Hospitalization System for the Northern district.

Daburiyya is a 10,000-person village populated by some of the highest rates of nurses and doctors per capita in the Arab society. I live here next door to the house I grew up in, where my parents live – my mother, may she live a long life, and my father, who sadly passed away during COVID-19. He died on March 13, at the peak of the COVID-19 crisis.

My father’s funeral was on Saturday, and I was on the phone the whole time. I barely even went to the mourning house. Finally, my older brother turned to me and said, ‘Listen – go. No one’s angry. Go out and do your work. They need you and we understand.’ The very next day, I was already in the office. I told everyone that if I had managed to come from my house to deal with the situation, everyone had to buy in. This was our moment of truth.

Then came a wave of morbidity in the area’s villages: Daburiyya, Kafr Kanna and more. An outbreak took place in a nearby nursing home called Yavniel. It started with one, two, three, four, five people, and then we discovered that almost house had someone who had been in contact with a confirmed patient or who was sick him or herself. It was then when Daburiyya began making the headlines.

Daburiyya’s mayor was smart; he knew who to contact. He picked up the phone and called everyone who works at Clalit and told them that he needed help. And he didn’t ask – he demanded. Daburiyya is not typically part of a zone I’m responsible for, but since I live here, I asked to focus my efforts here.

At the peak of the crisis, we set up a testing tent and began operating it. We set up three testing cycles in Daburiyya, and Clalit conducted around 700 tests. It was a true local collaboration – everyone put in a joint effort.

I don’t typically deal with Magen David Adom or the IDF Home Front Command on a daily basis. We only see each other when we run some sort of exercise or when the Ministry of Health conducts reviews – not the happiest of occasions. But suddenly, everyone became a partner around the same table. There were tons of opinions, many different customs and various political identities, but at the end of the day, we all wanted to help everyone. This type of collaboration is ultimately what will help curb the disease.

I think COVID-19 is the only situation where the State of Israel has truly been threatened and Arabs and Jews have stood side by side; Jews have trusted Arabs and we have worked together. We’re all behind masks. The hazmat suits we all wear have proven that our appearances have no real meaning. Our content and humanity have stood out more than anything. It doesn’t matter where you came from. That’s thanks to COVID-19. That’s the beautiful side of the coronavirus.”

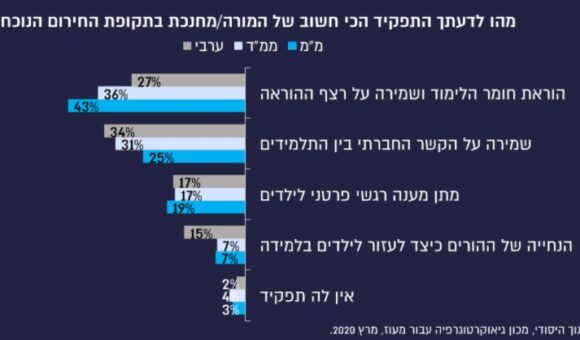

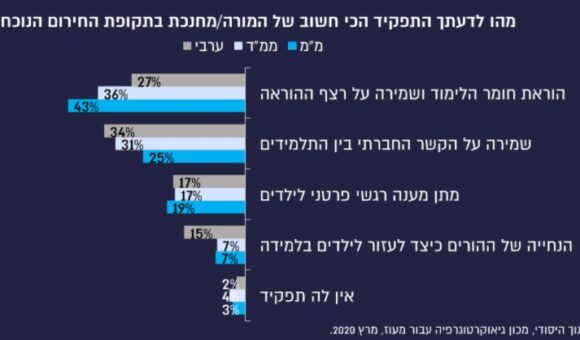

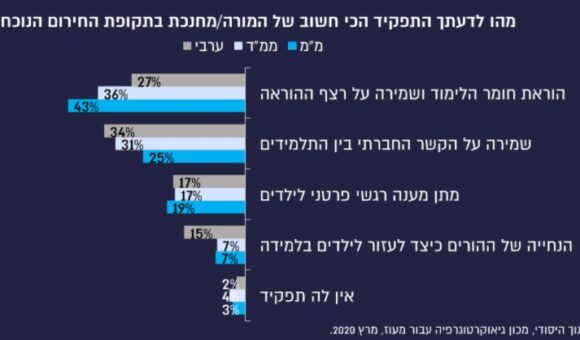

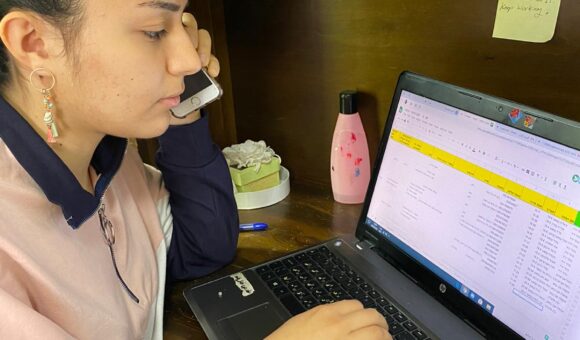

Parents Have a New Role. And We Have to Listen to Them

What happens to parents when the school system closes and the classroom is replaced by the living room? MAOZ’s ADVOT Joint Venture decided to find out with a survey, which was then delivered to policymakers

When the pandemic broke out and the country shut down, classrooms were left behind and studies became remote. The classrooms, teachers’ lounges, principal’s office and schoolyard were replaced by a single space: the home.

Parents discovered that they had a new role: they needed to be part-teacher and part-tutor, reinforcing their child’s education with private lessons. With no prior preparation, they were suddenly required to be much more involved and active in their children’s schedules.

How did they handle this? And what did they think of their new roles? What’s difficult for them? What works? What doesn’t? What could help? And what simply needs to change?

The ADVOT Joint Venture decided to find out what parents had to say. Thus the parent survey was launched, aiming to bring a new voice to the policymakers’ table. More than 800 parents took part in the survey, which sought to uncover attitudes and perceptions regarding distance learning.

The information was collected, organized, and transferred to the Ministry of Education and local authorities, with the aim of updating and adjusting the approach and implementation of distance learning. In Umm al-Fahm, for example, a Network member used the data to help in the process of holding meetings focused on increasing trust among parents. In the Ministry of Education, discussions about learning were held based on the insights obtained from the data.

The knowledge continued to circulate to the OECD research body, to other organizations which analyzed the data and distributed it to their audiences, and to media outlets which covered the story through the eyes of the parents. Following the general survey, a group of ultra-Orthodox Network members initiated a special survey for ultra-Orthodox parents, and the insights obtained regarding the reopening of schools between lockdowns were applied.

Spike in People Seeking Psychiatric Treatment Due to the Pandemic

In his clinic, Dr. Shimon Burshtein, a psychiatrist, sees many patients who wouldn’t have needed him if not for the pandemic. But now he can provide remote care to people in their natural environment

“Psychiatry is healthcare for mental illness. There are those defined as patients with psychiatric illnesses, such as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia.

And lately there are also many people who have never been diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, who have turned to mental health services due to distress. These are not people who have an illness that is defined as a mental disorder – they’re simply in psychological turmoil regarding the new circumstances they find themselves in.

There are two components to this: one is certainly the objective difficulties. When someone is anxious about whether his or her children will have food to eat tomorrow because his or her business isn’t running and there’s still a mortgage to pay, there is an objective difficulty and objective tension there. The second component is the distress arising from the uncertainty, and the fact that he or she doesn’t know what will happen.

People have depleted their reserves, causing distress levels to rise. Then, if they want to make an appointment with a psychiatrist, they discover that the next opening is in three months. It’s when our lack of availability has heavy ramifications, such as suicide attempts, that I have the hardest time. I say to myself: ‘if I had been available, would the outcome have been different?’ The very question is problematic because it arouses guilt and frustration in me.